Types

There are many types of shot, and there are several ways to categorize different shots.

Shots can be classified by implied proximity, the implied—not physical—distance between the camera and the subject. Modern cameras need not be physically close to a subject to produce a close-up shot. Extreme long shots provide spatial contexts, long shots feature both the subject and the background, medium shots show characters typically from waist up with enough headroom, the medium close-up frames characters from the chest up, and close-up shots focus on the character’s face with a great deal of detail. Extreme close-up shots would fill the frame with a detailed part of a character’s body or face (such as hands or eyes) or an important part of an object (such as a knife or a key).

Shots can also be described based on the roles they play in a sequence, such as establishing shots to indicate when and “where we lay our scene” (time period and setting) as the Shakespearean Prologue to Romeo and Juliet announces. An establishing shot could involve aerial views of a city, for instance.

There are also point-of-view (POV) shots showing what a character sees. POV shots are often followed by reaction shots showing the facial expression of the character.

There are a number of ways in which film editors link together various shots. They could connect two shots of the same subject with a jump cut to create a sensation of jumping forward in time.

They could also connect two shots through the fade transition with the first shot fading out and the second shot fading in.

Examples

Sexism and Film

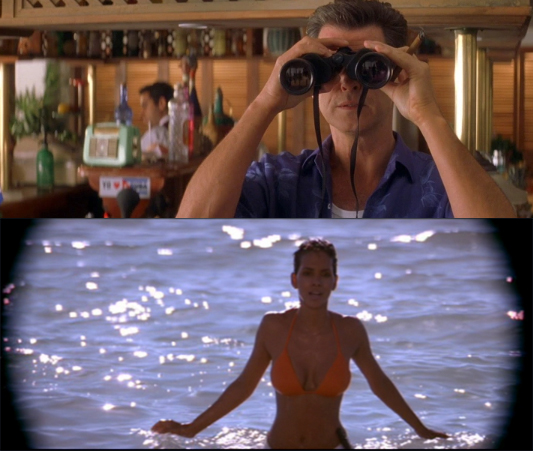

Masculine Point of View (POV) shots sometimes objectifies female characters if it is a male character who is doing the looking. This type of shots puts film audiences in the male character’s perspective and treats that perspective as a default, as exemplified by Lee Tamahori’s Die Another Day (2002), which is part of the franchise of James Bond, based on Ian Fleming’s novels.

In the film stills and film clip above, from Die Another Day, Jinx comes into existence through James Bond’s eyes and binoculars. Film audiences meet Jinx in a POV shot through the binoculars.

This scene pays homage to the very first James Bond film: Dr. No (dir. Terence Young, 1962) where the “Bond girl,” Honey Ryder (played by Ursula Andress) emerges from the sea. Bond (played by Sean Connery) happens up on the scene of her collecting sea shells and is mesmerized by her beauty. Watch the scene here.

Just as lighting, slow pan or tilt (see the lesson on Camera Movement), and fragmentary framing disconnect characters from their environment, POV shots make the characters more sensual.

Shooting Disabled Figures

POV shots can also heighten a character’s anxiety as someone who is being scrutinized.

Tom Hooper’s The King’s Speech (2010) employs a series of POV shots and reaction shots to portray a disabled figure’s anxiety about his vocal disability. The film dramatizes the relationship between Britain’s King George VI (Colin Firth) and his speech therapist Lionel Logue (Geoffrey Rush) in the 1930s. The king stammers and is ill-equipped to deal with the new role expected of the monarch in the then nascent era of radio.

As Alexa Alice Joubin points out, “before we hear vocal disabilities of a stuttering or mute character, we first see and register visually his anxiety.” The film opens with a speech at the Wembley Stadium in 1925 given by a nervous Prince Albert, Duke of York (known as Bertie, later King George VI). Bertie’s stuttering is exacerbated by his stage fright, which is triggered by the mic.

The menacing presence of the mic magnifies his deficiencies. Film audiences are initially placed in Bertie’s perspectives as he approaches the stage, locking eyes with the large microphone.

This POV shot shows how the carbon ring microphone and the crowd intimidate Bertie.

A reverse shot takes the perspective of Bertie’s audiences at the stadium.

An extreme close-up makes the carbon ring microphone appear larger than Bertie’s face.

His eyes are fixated upon the imposing device, and his posture unnatural. The absence of soundtrack and diegetic sound conveys Bertie’s fear, which is framed by the imposing ring microphone.

Further Reading: Alexa Alice Joubin, “Screening Social Justice: Performing Reparative Shakespeare against Vocal Disability,” Adaptation 14.2 (August 2021): 187–205. particularly pages 195-198.

Exercise

The following shot depicts the aftermath of a shipwreck and what the survivors are going through. This is one of the early scenes in Adam Smethurst’s Twelfth Night (2018).

Watch this clip and analyze how different shots convey Viola’s (played by Sheila Atim) anxiety as a refugee in Illyria, a foreign land.

Answer Key provided in class.

Further Reading

- Quendler, Christian. The Camera-Eye Metaphor in Cinema. New York: Routledge, 2017.