Definition

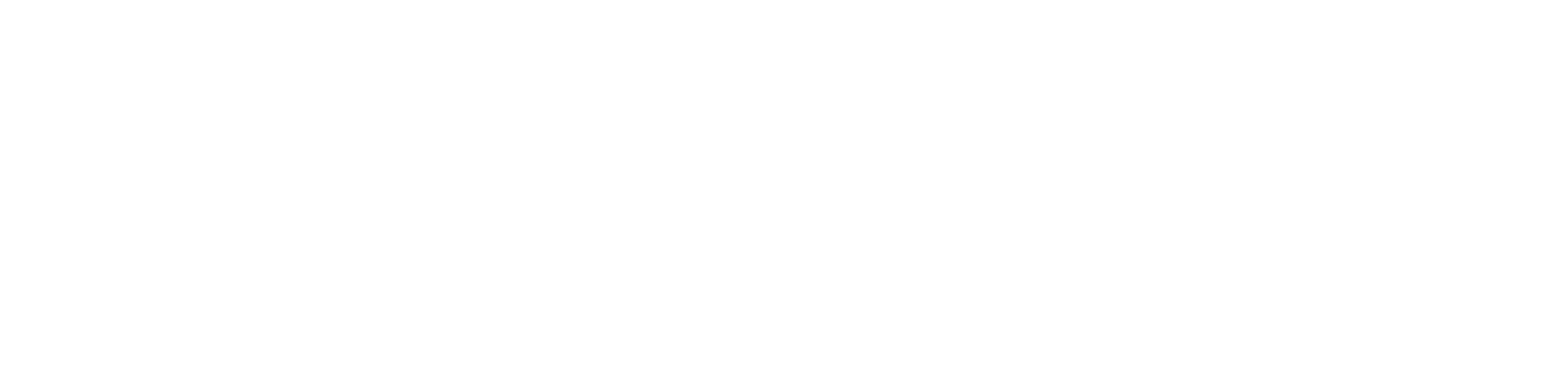

A film adaptation transfers a dramatic or literary narrative to the cinematic form. Far from being “derivative” or a secondary form of art, film adaptations are highly original artistic ventures. An adaptation achieves far more than simply visualizing a textual narrative. The following diagram shows one of the misconceptions about adaptation, with a so-called original text on the left and a “product,” a film adaptation, on the right.

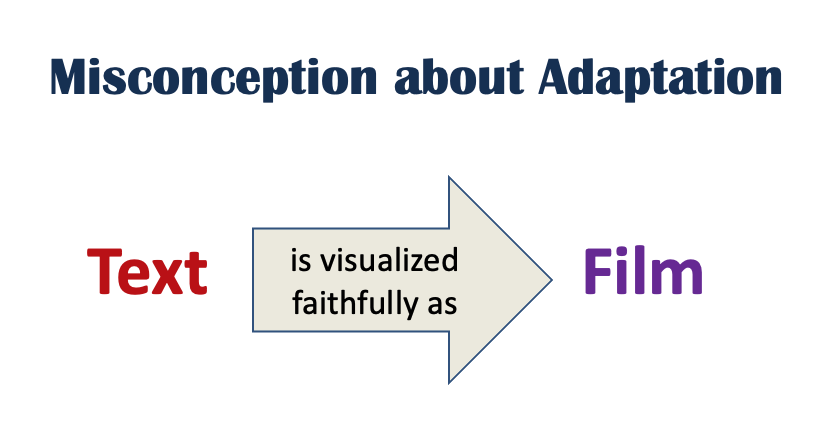

Scholars such as Thomas Leitch, Linda Hutcheon, and Robert Stam have regarded adaptation as a dialogic process. Adaptations of literature are in dialogue with pressing social issues of our times and with past literary masters.

The following non-hierarchical honeycomb diagram shows what really happens in adaptation. As shown by the diagram, an adaptation is part and parcel of many texts, intertexts, and pragmatic concerns. The so-called “original” text is merely one part of this network of cultural resources rather than a point of origin for artistic creativity.

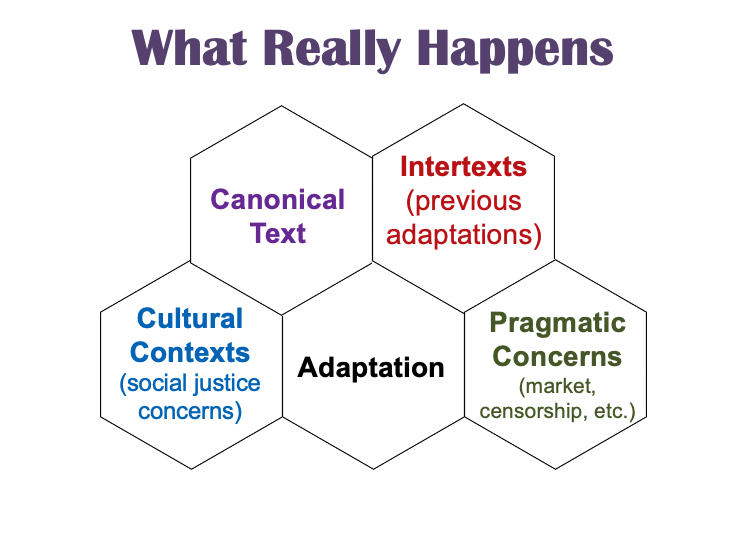

When there are multiple adaptations of the same story, these adaptations form a network of cross-references and enter into intriguing conversations with one another. Adaptation may even form a self-reinforcing feedback loop, as shown by the following diagram. What is perceived to be canonical or important will be more frequently performed and adapted. The stories that are more frequently adapted will then become better known and more widely circulated. As a result, these stories will become more canonical.

Therefore, it is more productive to examine adaptations as works of art in their own right rather than to conduct a survey of how “faithful” an adaptation may be to the “original.” Think of film adaptation as a vital part of an ongoing dialogue with history.

Examples of Film Adaptation

Examples of film adaptations of distinguished or historically important works include Greta Gerwig’s adaptation of Louisa May Alcott’s novel Little Women (2019), Steve McQueen’s Twelve Years a Slave (2014 Oscar Best Picture award), based on the abolitionist Solomon’s memoir, Cary Fukunaga’s 2011 Jane Eyre, based on Charlotte Brontë’s novel, Ang Lee’s Sense and Sensibility in 1995, based on Jane Austen’s novel, Robert Zemeckis’ Forrest Gump (1994), an award-winning adaptation of Winston Groom’s novel, and Baz Luhrmann’s 2014 The Great Gatsby, based on F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novel.

Literature has always been a source of inspiration for the film industry. In fact, when film was invented, the genre competed with theatre as high art. Filmmakers drew on classical literature to legitimize their creative work. The literary canon is seen as a proven source of archetypal stories with enduring cultural resonance.

Film adaptation is both a trans-historical and trans-genre enterprise. Adaptations may change the historical setting of the works. Adaptations may also change the genre from a novel to a narrative film, or from tragedy to parody.

Your Turn: What is your favorite film that is an adaptation? Why?

Film Adaptations of Shakespeare

In particular, Shakespeare’s words have often been used as proof of concept or launch material for new technologies, such as radio and early cinema. Shakespeare played an important role in the birth of film as an art form. Directors of silent film drew on the canonicity of Shakespeare to validate and legitimize their new art form when only theatre was widely regarded as highbrow.

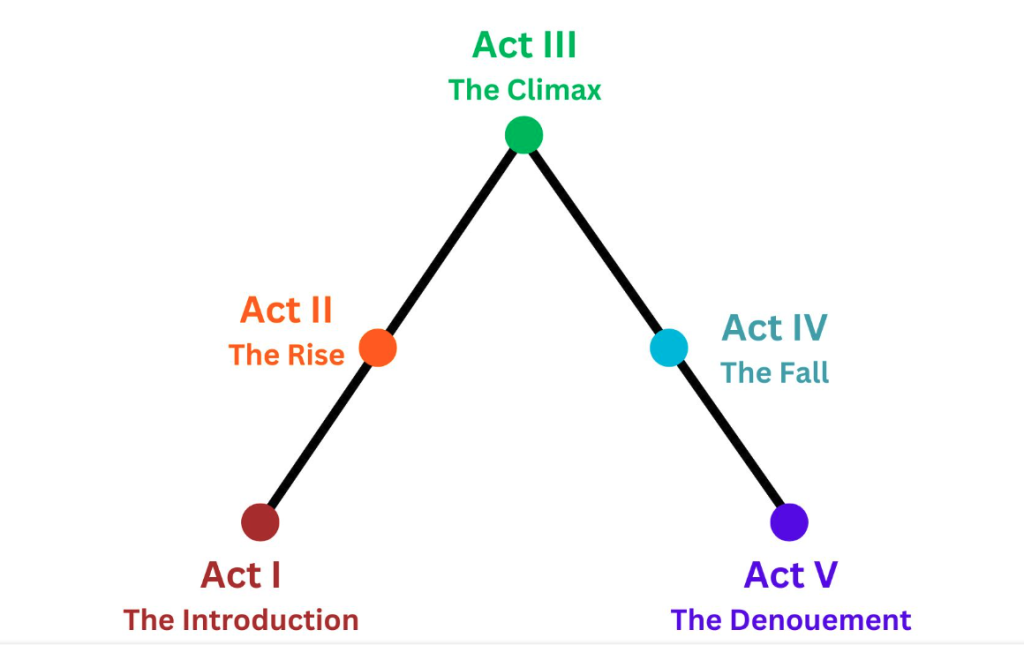

Since Shakespeare wrote for the stage, there are some structural differences between theatre pieces and screenplays. Notably, Shakespeare follows a five-act structure in developing the dramatic narrative, proceeding from an introduction (action may begin in medias res; audiences are dropped into the middle of an unfolding story) and proceeding through rising tensions to a climax and some form of resolution (the denouement).

Inspired by Aristotle’s work, German playwright Gustav Freytag came up with a pyramid to explain this five-act structure, as shown below (Technique of the Drama, 1863; read it on Open Library).

Like theatre, cinema is also a structured narrative governed by genre conventions. While drama is typically divided by acts that unfold synchronously in front of a live audience, film proceed through scenes that are governed by filming needs and finalized in post production through editing and other processes.

Take, Romeo and Juliet, for example. Act 1 introduces the ancient feud between the Capulets and the Montagues through the conflict between servants of the two households. A lot of the dramatic action here paves the bumpy road to Romeo and Juliet’s eventual meeting in Act 1 Scene 5 to discover, to their horror, they are “star-crossed lovers” and that their parents would never approve of their relationship. Films often take liberty with sequences of events in favor of flashbacks.

The history of Shakespeare on film begins with the invention of film as a new medium in the late nineteenth century! The history of Shakespeare parallels the history of film. Samuel Crowl divides the history of Shakespeare on film into the following phases:

- Silent film era

- Hollywood’s early experiments with sound

- An international expansion of Shakespearean filmmaking after World War II (notable directors include Laurence Olivier and Orson Welles)

- The golden age of televised Shakespeare

- The age of commercial feature films in late 20th century.

Here is an example from 1909, a silent film adaptation of A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

A Midsummer Night’s Dream, a silent film co-directed by Charles Kent and J. Stuart Blackton in 1909. Source: Vitagraph.

In 1944, Laurence Olivier produced the first screen adaptation of Henry V to encourage British patriotism during World War II. In contrast to his predecessors who primarily filmed stage productions, Olivier—as an established actor but a first-time film director—designed his film to be “cinematic” in the sense that he treated film not as a documentary tool of the stage but as a comprehensive art consisting of camera work, blocking, soundtrack, and many other elements.

There are now hundreds of films that are based on or have been inspired by Shakespeare’s comedies, tragedies, and history plays. There are ready audiences eager to see their favorite stories on screen. Film adaptations do not so much “replicate faithfully” what Shakespeare wrote. Rather, films give us new pathways into familiar stories and thereby shed new light on what we took for granted.

Here is a short lecture on the history of Shakespeare on film by Professor Joubin. The lecture covers the key phases of adapting Shakespeare to screen.

Adaptations may shift the perspective through which a well-known story is told. Claire McCarthy re-told the story of Hamlet from the perspective of his love interest, Ophelia, in her 2018 Ophelia, a feminist retelling of the famous character from Hamlet. The film is based on Lisa Klein’s novel and stars Daisy Ridley (of Star Wars fame; she played female Jedi Rey Skywalker).

Claire McCarthy’s Ophelia (2018)

Adaptations may also amplify historically suppressed themes within a story, often with artistic flourishes such as dramatic lighting or music. An example is the emphasis on feminism and Romeo’s “soft masculinity” as performed by Leonardo DiCaprio in Baz Luhrmann’s William Shakespeare’s Romeo + Juliet (1996).

Your Turn: What are the challenges in adapting canonical literature to the screen?

Further Reading

- Cartmell, Deborah, ed. A Companion to Literature, Film, and Adaptation. Hoboken, NJ: Blackwell, 2012.

- Desmet, Christy, Sujata Iyengar, and Miriam Jacobson, eds., The Routledge Handbook of Shakespeare and Global Appropriation. London: Routledge, 2019.

- Hutcheon, Linda. A Theory of Adaptation, 2nd edition. London: Routledge, 2012.

- Iyengar, Sujata. Shakespeare and Adaptation Theory. London: Bloomsbury, 2023.

- Leitch, Thomas. Film Adaptation and Its Discontents: From Gone with the Wind to The Passion of the Christ. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007.

- Sanders, Julie. Adaptation and Appropriation, 2nd edition. New York: Routledge, 2015.