Taking Screening Notes

Film as an immersive medium is designed to make its conventions of artificial reality “invisible” to the viewers. Our first task is to see beyond what Dave Monahan and Richard Barsam have called “cinematic invisibility.” Watch a film at least twice so that you can reverse engineer some of its key scenes.

Here is a short lecture on film analysis by Professor Joubin. This four-minute lecture covers the key elements in film making and three major strategies of adapting literature to the screen.

On your first viewing, you may be immersed in the fictional universe or surprising twists and turns of the plot. Your second and third viewings will offer artistic distance for critical analysis and for breaking down a sequence frame by frame, edit by edit. How did the production team put together the scene? Consider elements such as casting, blocking, costuming, the set, cuts, camera work, diegetic and nondiegetic sounds and music. Why did the filmmaker frame the scene in this particular way?

Here are some sample screening notes. Note as much detail to a scene as you can. This will provide a foundation for the next step: critical analysis.

Much Ado About Nothing, dir. Kenneth Branagh, 1993

In the film’s long opening sequence, a lot of characters are showering, including men and women in their separate “camps.” Note the rapid intercutting between female and male characters in the bathing sequence. This juxtaposition sets up gendered “camps,” parallels, and oppositions. It echoes the “merry war” between men and women, “betwixt Signior Benedick and Beatrice.”

Shakespeare in Love, dir. John Madden, 1998

As part of the film’s opening sequence, we meet Shakespeare hard at work at his desk, except he isn’t writing (he is suffering from writer’s block). He merely practices signing his name in various styles. This scene seems self-consciously kitschy. There is a modern (time traveling?) mug souvenir from Stratford-upon-Avon

King Lear, dir. Richard Eyre 2018

1:05:00 Edmund puts his hand on Regan’s derrière. It’s one of the first signs that Regan is having an extramarital affair (husband seems oblivious at this point).

1:35:00 Gloucester dies in an empty house during bombardment with Edgar by his side. Gloucester touches Edgar’s face, hinting at his recognition of his son. Edgar interrupts his father’s second suicidal thought (the first was at the Dover cliff) by saying “Men must endure their going hence, even as their coming hither: Ripeness is all.”

“Ripeness” has special religious significance in this context. A point for further reflection.

Keep in mind that there is no single, correct method of taking screening notes. These suggestions are simply meant to demonstrate how an initial set of brief and apparently disconnected observations served as an important reminder of the range of cinematic elements.

Writing an Alt Text

Another useful exercise in preparation for critical film analysis is writing alt texts. Alt texts, or alternative texts, are textual (verbal) descriptions of images and videos that enhance web accessibility and equity. Alt texts meet the needs of individuals with print, visual, cognitive disabilities.

Visually impaired users using screen readers will hear the description and better understand the image. Alt texts are also very useful when an image link is not available because of a broken or changed URL or other issues.

Writing alt texts deepens our grasp of a film. The first step towards critical analysis is an accurate, detailed description of our object of study. This exercise is also part of our collective pursuit for equal access and social justice.

However, alt texts are often dismissed or understood through the lens of compliance, as an unwelcome burden to be met with minimum effort. We can instead approach the alt text thoughtfully and creatively.

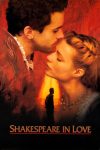

Let us give it a try. Describe the following film still with as much useful detail as possible. The film still comes from Shakespeare in Love. This scene is both theatrical and cinematic.

There are several ways to describe a frame. Balance technical details with artistic and interpretive descriptions of the shot. Technical details include the mise-en-scène and cinematographic information such as the depth of a shot or camera angle. Artistic elements include aspects of the shot that are open to interpretation, such as a character’s mood or how much a scene contributes to social justice causes.

You may opt to describe various elements in this image in the order in which audiences typically perceive them (for instance, noting characters or items in the foreground before moving on to the background).

You may opt to include or omit actors’ and characters’ names (such as Joseph Fiennes playing Will playing Romeo and Gwyneth Paltrow playing Viola de Lesseps playing Juliet).

You may keep the contextual information to a minimal and instead note technical details of the composition of the shot.

You may note the irony of the couple embracing each other upstage, seemingly still in character, while their fellow actors are bowing to audiences in the background downstage. The show is over, and it is time for curtain call.

Here are some examples of alt texts for this image.

In the foreground, we see a couple in Elizabethan clothing embracing, with a woman sitting on a man’s lap. She is cradling his head, with her fingers nestling into his short brown hair, while he has his arm wrapped around her waist, just below her long, blonde curly hair. They are staring deeply into each other’s eyes. In the midground, in soft focus, we see performers with their backs to us, bowing before an audience. In the background, we see a blurry sea of faces, both on the ground, and on the balconies above.

The crowd claps and cheers, standing along the banisters in the multi-level theater as the actors receive their applause. At the front of the frame, a curly haired blonde wearing a golden long-sleeved gown stares admiringly into the eyes of Will Shakespeare as she places her hands around his neck. Shakespeare supports her in a kneeling stance with his arm around the back, gazing lovingly back and preparing for a kiss.

In the foreground, Gwenyth Paltrow’s character and Joseph Fiennes’ character hold each other lovingly, staring into each other’s eyes. They have just ended the play and sit off-stage, while the other performers take their bows. In the background, a packed house inside the Globe Theatre gives a standing ovation for the performance.

Two actors attired in ornate apparel embrace, eyes locked, facing each other. The character with long blonde hair holds the character with a beard’s head; the latter rests their hand on the former’s back. They are off-center. In the background, other characters are on stage with their backs to us. They too are attired in Elizabethan garb. In the background, blurry, are the audience members: standing, applauding, they are facing us in the galleries of the semi-open-air theatre.

We can also write alt texts for an entire scene or short video. For example, write a first-level alt text for the following trailer of Shakespeare in Love.

Here are some sample alt-texts for this video.

Fast-paced string instruments underscore the tension described by the narrator (Shakespeare’s creative flops, financial trouble, threats from gangsters). We see short clips of Shakespeare struggling to write, actors fumbling through their lines, and menacing figures approaching the theatre. These scenes are peppered with moments of comedy (slapstick, references to famous lines).

Orchestral music builds the tension of the protagonist, Will Shakespeare, who is pictured with an often frustrated and tense browed expression as he storms through the streets, crumples his writing drafts, and reacts to his actor’s flub on stage. The violin increases in volume and speed as the threat of Will’s safety is described by a deep voiced, ominous narration of the urgency of his success in saving his career and threat of his physical safety against gangsters moving in the streets.

Across the movie trailer, we hear a portion of Vivaldi’s Four Seasons playing behind a deep male voiceover. The visuals cut between several shots, establishing the setting as Elizabethan London. The subject of the trailer is a frustrated William Shakespeare, evidently struggling as a playwright. The quick cuts and dramatic non-diagetic sound establish a frantic and disjointed tone.

Film trailers in each era have their own conventions. Read more about film trailers in Keith Johnston’s Coming Soon: Film Trailers and the Selling of Hollywood Technology (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2009).

Alt-Text in Film

Did you know that the popular trope of police sketch in crime drama is a form of alt-text? Typically an eyewitness would describe verbally, from memory, the main features of the face of a perpetrator. A sketch artist or, in more recent films, a computer facial composite specialist would generate a graphical representation of the suspect in question.

In a comic scene in Season 1 Episode 3 of Killing Eve (Phoebe Waller-Bridge, 2018), Eve (played by Sandra Oh) describes in detail an assassin’s features as the police attempts to create a facial composite on a computer. As it turns out, Eve and the technician are working at cross purposes. Despite Eve’s impressively elaborate and precise description, all the technician wants to know is if the assassin’s face is square or oval.

Key Elements

Here are some key elements you may consider while analyzing a film: mise-en-scene and setting, cinematography, and sound and music.

- Scene composition

- Lighting

- Blocking

- Camerawork

- Shot type and duration

- Transition type

- Soundtrack or the lack thereof

- Screenplay

Questions to consider include the following:

What is the setting? Where is the scene taking place? What do props and costumes tell us about the time period, about the characters and their social standings? What do these directorial choices reflect the director’s interpretation of the scene?

How does pacing change the meanings of the story? Does the film’s action drag on at any point? How and why? How does the speed or lack of speed affect your interpretation of the film?

What does the actor do with their voice? Do they use accents?

In terms of blocking (director’s planned movement for the characters on set), where do the actors stand (in relation to each other) in significant scenes? Does the camera focus your attention on one character more than on another by special blocking?

How often are there cuts and transitions? How long does the director stay with shots? When are there close ups, long shots? To what effect? How are emotions conveyed (cued by the soundtrack, by camera work)?

How is music used (sparingly, excessively as a guide to audiences, counterintuitively against the visual cues)? Are there scenes without nondiegetic soundtracks? What is the significance of silence?

What is the effect of each of these aspects on the scene being depicted? How does each director establish a tone for the film? To what genre does this film belong: action, thriller, historical chronicle, philosophical drama? What are the themes or leitmotifs of the film adaptations? Ambition, love, revenge, misogyny, friendship, betrayal?

Does the film remain open-ended or insists on a specific interpretation of the story?

Film analysis is distinct from film review.

Film analysis is distinct from film reviews. A film review is essentially a judgment about the quality of the movie, backed up with enough information to indicate the journalist’s judgment is based on good reasons.

Film analysis, however, is argumentative, and evaluation is far from central. You need not like a movie in order to say something insightful about it.

Good film criticism is more than a simple “thumbs up” or “thumbs down.” A good argumentative film essay analyzes as closely as possible the elements that constitute the film’s overall meaning. Your description of the film paints a vivid picture in the reader’s head.

But this description serves a clear purpose: it shows how filmmakers give the story cultural significance by using a variety of cinematic techniques (slow tilts, intercuts, depth of field).

Here are some examples:

Unhelpful description of a shot

Medium shot of a woman standing outside. Cut to a close-up of a dress behind a window.

More useful description

After a medium shot of a woman standing outside a window, the film cuts to a close-up of a dress behind the window.

Even better description

An eyeline match links a medium shot of a woman looking into a shop window to a close-up of a dress inside. This shot/reverse shot structure reveals her desire for the dress, and prompts the viewer to share this desire.

Screenplay

Writing and Analyzing Screenplays

A screenplay is the blueprint, or the script, for a film or television show. Screenplays typically include

- characters’ names

- dialogues

- actions

- sets

- stage direction

- indications of how characters should speak the line

- camera angle and movements

- music cues

- transitions

- and other cinematic elements.

Screenplays follow an industry standard format which is important in the filmmaking process. Properly formatted screenplays aid in the script and scene breakdown process (a key process in turning a script into a film), budget planning, casting, and shooting scheduling.

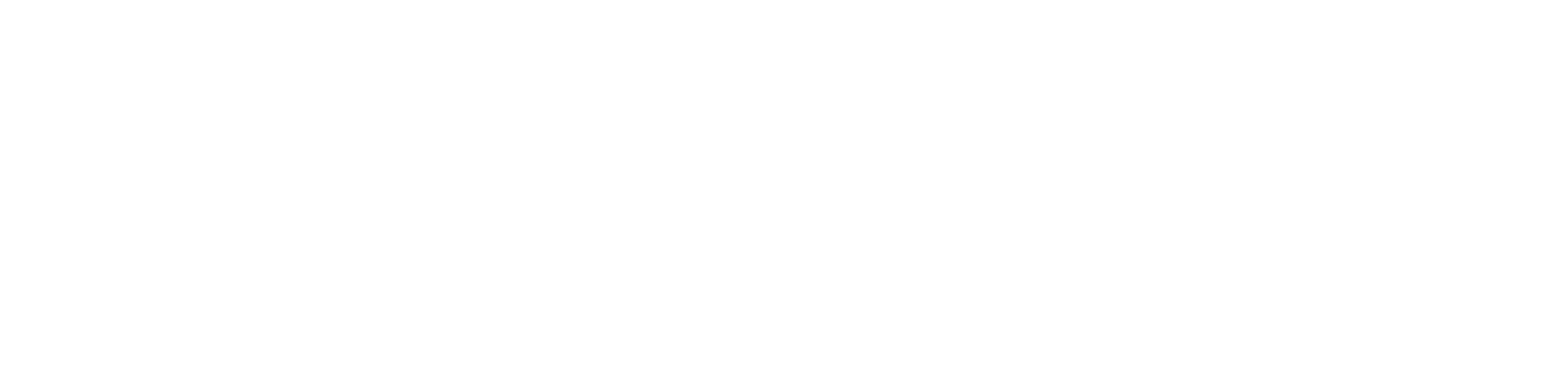

The best way to understand screenplays is to write one yourself. Let us demystify the screenplay format and elements. Here is a sample screenplay with some key elements highlighted. You would typically begin with a heading indicating the key location and time, followed by a description of what the characters are doing before the dialogue begins.

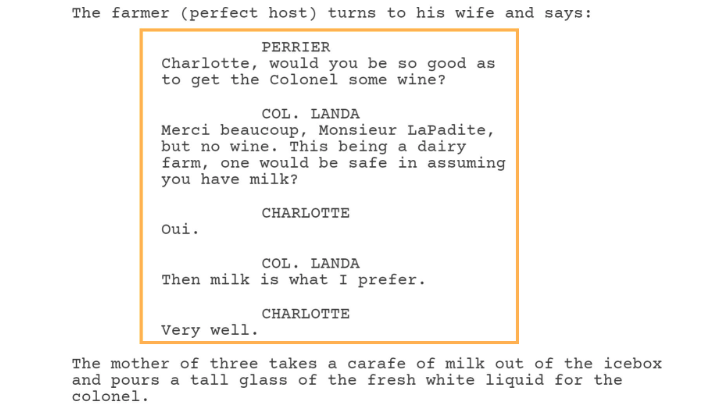

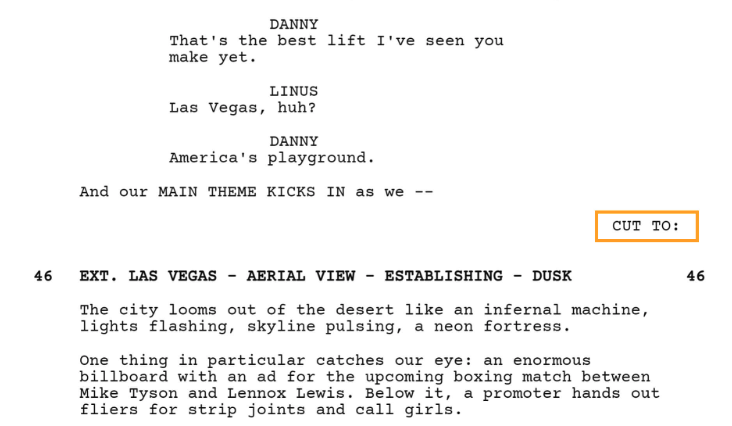

Here is another, more comprehensive example of a screenplay, showing more elements in formatting and scriptwriting. Let us take a look at each element.

After the list of dramatis personae, the first element is the slugline, also known as a scene heading. This section indicates the location and time of the action. This information is important for the purpose of continuity in terms of makeup, hairdo, and costumes. For example, does the scene take place at night or during the day? The same day?

Immediately below the scene heading is the action. It is always written in the present tense and as visually descriptive as possible. This section indicates what viewers will see and hear in the finished film other than dialogue. This section includes anything from a fight scene (without dialogue) and establishment shot showing the setting to all other cinematic elements.

The next important element is your character’s name or “ID.” Center the name and capitalize it. Dialogue starts in the next line. Your character ID need not be your character’s full name. It could be a first name, a last name, or an alias. Just stay consistent. One exception: if your character goes into disguise, then you’d indicate both names. For example, when Bruce Wayne (WAYNE) becomes Batman, you would write: WAYNE/BATMAN.

The next element is the dialogue. See this example below:

The characters would typically speak for themselves without heavy-handed “explication.” They show us who they are by the words they use, for example. In terms of formatting, there are margins on either side of the dialogue (which is in the center) to allow for notes later.

Not all dialogues occur when characters are within the camera’s frame. This is where extensions come in. Extensions go next to a character name in parentheses. Extensions tell us how the dialogue is heard by the audience (off screen, on the phone, etc.).

Dialogues may be interrupted, and this is when CONTINUED (or CONT’D) comes in. You would write CONT’D next to the character’s name to indicate the continuation of their lines after they have been interrupted by some action.

What if a dialogue for the next scene starts as the current scene is fading out? Write Pre Lap in the parentheses next to the character’s name.

There is more to the vocal soundtracks beyond dialogues between characters. For example, use Voice Over (V.O.) to indicate that a character is speaking over the action but is not heard by other characters in the scene. V.O. is typically a kind of narration, but it can also be a character’s internal dialogue in a montage.

OFF SCREEN (O.S.) indicates that a character is speaking and is heard by other characters, but can’t be seen by the audience or other characters. Again, put O.S. in parentheses next to a character’s name. You may also use Off Camera (O.C.). This could be someone making an announcement over a loud speaker or a disembodied ghostly voice.

Next, let us take a look at transitions. Here is an example:

In the example above, from Ocean’s Eleven, screenwriter Ted Griffin uses CUT TO to emphasize the switch of location to Las Vegas. The dialogue builds momentum going into the next scene. Note the vivid description of Las Vegas in section below CUT TO.

Put transition indicators on the RIGHT side of the page (right justified). Screenplay transitions indicate how an editor should switch between two scenes. Other possibilities beyond CUT TO include DISSOLVE TO, INTERCUT, and CROSS-CUT.

Here are screenplays of two renowned films:

- Shakespeare in Love (co-written by Marc Norman and Tom Stoppard)

- Richard III (written and performed by Ian McKellen)

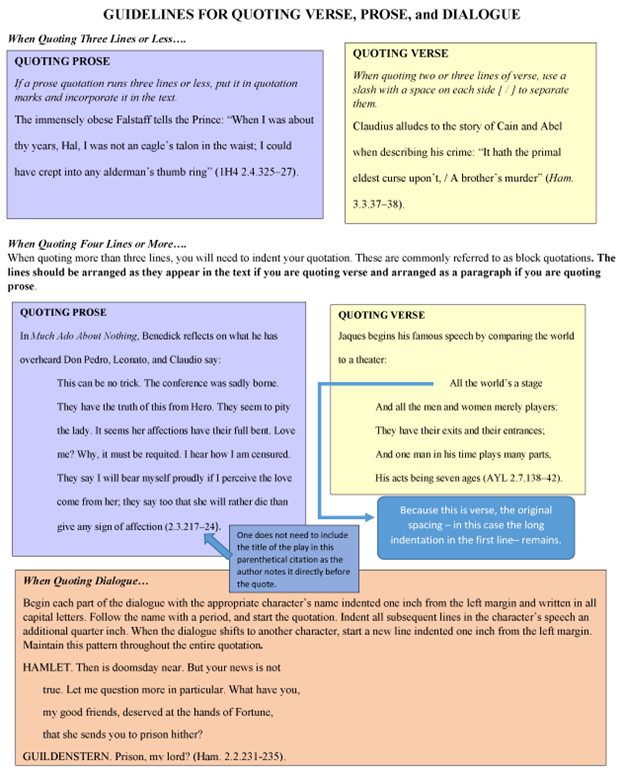

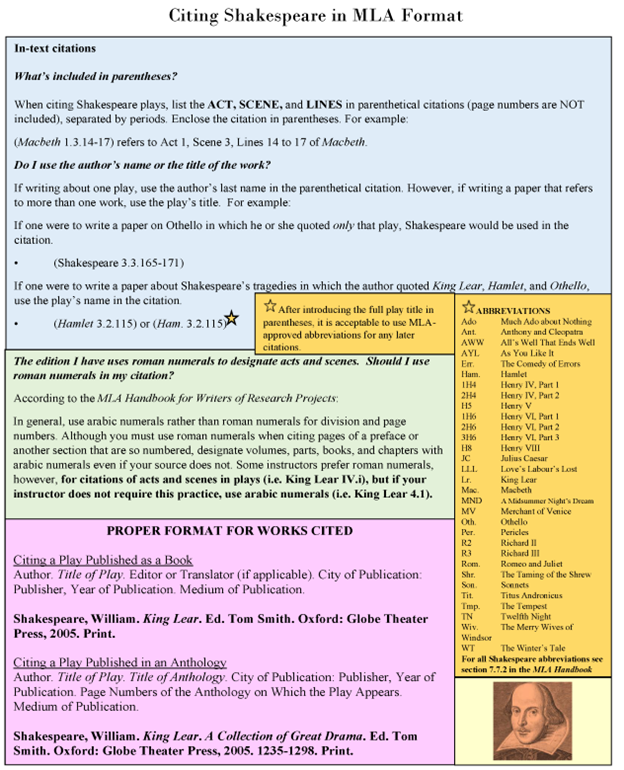

Citation Style

Last, but not least, here are some guidelines on quoting verse, prose, dialogue, and Shakespeare (in the MLA format).

Further Reading

- Ed, Sikov. Film Studies, second edition. New York: Columbia University Press, 2020.

- Egoyan, Atom and Ian Balfour, eds. Subtitles: On the Foreignness of Film. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2004.

- Johnston, Keith. Coming Soon: Film Trailers and the Selling of Hollywood Technology Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2009.